What did Jesus really look like?

I have written previously about whether Jesus had a beard, and 3 years agone commented on the discussion past Joan Taylor (of King'south College, London) well-nigh what Jesus looked like. Joan has at present produced a terrific volume drawing together her research, and the book takes the states an intriguing journey into how people thought virtually Jesus.

I have written previously about whether Jesus had a beard, and 3 years agone commented on the discussion past Joan Taylor (of King'south College, London) well-nigh what Jesus looked like. Joan has at present produced a terrific volume drawing together her research, and the book takes the states an intriguing journey into how people thought virtually Jesus.

The opening chapter explores a serious puzzle in the New Testament, i which nosotros are so used to that we do not even realise that information technology is there. Why do the gospels accounts include no description of Jesus' appearance? There is a view around that the gospel writers were not eye-witnesses and so did not know, and that the gospels asancient 'lives' were non concerned with such questions, since the question of Jesus' appearance have no bearing on thistheological importance. But Taylor demonstrates how mistaken such assumptions are. She agrees with the position (promoted by Richard Bauckham) that the gospels are connected with center-witnesses, so it would take been possible to include a description of Jesus. But she offers three reason why we might expect to take some clarification of Jesus included.

The first relates to the gospels as first-century 'lives', every bit demonstrated past Richard Burridge some years agone. The verbs heart on the action and teaching of the principal graphic symbol, Jesus; the account is non linear, but gives item focus to centra, revealing events; and a primal focus is the fashion the main graphic symbol dies, telling u.s. the well-nigh of import thing about their life. But, Taylor notes, other 'lives' of the time consistently do refer to the appearance of the heroes they draw—a good instance being Suetonius who describes Augustus as 'unusually handsome and exceedingly svelte at all periods of his life'. Though she does not mention this explicitly, it is part of the Greek tradition summed upward past the phrasekalos kai agathos:

In a strict sense kalos kai agathos only means "beautiful and proficient," but a better rendering would be "fine and noble," or "superior and excellent," or even "the best that a man can be." The phrase was used to refer to an ideal of life and behavior that every Greek cherished for himself, even if he could not embody it totally.

The outward, noble appearance of someone communicates the person'south inner virtue. This conventionalities in the importance of appearance extended to contemporary Jewish views of Moses, who was thought to be alpine and proficient-looking—fifty-fifty when he was merely three years old! Only this opens up the 2nd factor—that the biblical record in the OT also notes how handsome the leaders and kings of Israel were. Joseph was 'handsome in form and appearance' (Gen 39.6); Moses was indeed a beautiful babe (Ex 2.2); Saul was exceptionally tall and handsome (ane Sam 9.ii); though Samuel is not to choose his successor on the basis of looks, withal David is also very bonny (i Sam xvi.12); and David'southward son Absalom is fantastically attractive (2 Sam 14.25–26). If Jesus follows Joseph in being harmed by his people, but through that saving them from disaster, if he is the new Moses (as Matthew, organising his education into five 'books', would have it), if he is the true Davidic rex—how surprising that the gospel writers ignore this of import tradition.

But the third issue is the most intriguing. The gospel writers, and especially John, are emphatic about the physical reality of Jesus, the Word who 'became mankind and tented among us' (John i.xiv). John tells u.s.a. that Jesus was hungry and thirsty, that he was misunderstood and lauded, that he wept at the loss of a friend, and that the 'honey disciple' (almost certainly John himself) leant on his chest whilst dining—and yet we are told nix of the 'flesh' itself. Function of this is the gospel's theology of sight, summed up in both John vii.24 ('Do not approximate past appearances'), the healing of the homo built-in blind in John 9, and the summary conclusion in John 20.29, where seeing is not assertive just assertive is the true seeing.

Taylor then takes us on a journey through a number of traditions of the depiction of Jesus in art. The kickoff is what she calls the 'European Jesus', the image that comes up immediately if we do an internet search for images of Jesus, which is expressed in Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi, and which has frequently shaped motion picture depictions in Western productions. She traces this image to a description in the fourteenth-century Letter of Lentulus, supposedly written past a first-century eye-witness of the gospel events, just full of historical anomalies. The most concerning attribute of this popular depiction (in ane form, by Warner Sallman, distributed to all American service personnel in the 2nd World War), is that it removes Jesus from his historical context as a Jew—though the Jewishness of Jesus has been at the centre of academic study for the terminal 50 years.

The 2nd tradition is quite distinct, and is associated with Veronica, supposedly the woman who was healed from the outcome of blood (Mark 5.29) who (likewise supposedly, wiped Jesus' face with a material which was and so imprinted with his image. Taylor does a forensic task in tracing how this story arose from a misinterpretation of a third-century bronze statue of Asclepius and Hygeia, which is interesting in itself.

The third tradition of Jesus' image is perhaps the almost well-known. It relates to what are known asacheiropoieta, a Greek phrase significant 'not made by human easily', which are images fabricated as imprints of Jesus—the near famous being the Shroud of Turin. After exploring other earlieracheiropoieta, Taylor gives a good summary of the issues relating to the Shroud, including noting that the weave of the textile is clearly mediaeval, the issues around the pigmentation, and the fact that its description as asudarium or 'sweat-cloth' is historically anomalous. She concludes with an intriguing thesis: that this was indeed a burying fabric, and that the marks have indeed come up from a human corpse, merely that it is from a mediaeval pilgrim who sought to imitate Jesus in his death (compare Phil 3.ten…!), so that the image actually tells us what people in the 13th century thought Jesus might have looked like. Equally with previous traditions, the connection with the historical Jesus falls curt.

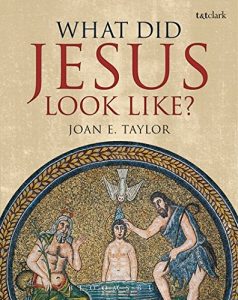

The next 2 traditions accept us back much earlier, to the fourth century: the image of Jesus equally 'Almighty', depicted every bit ruler of the world (cosmokrator or to apply the biblical termpantokrator); and the image of Jesus as 'male child wonder', a youthful god-like figure (which includes the image from Ravenna on the encompass of the volume and shown at the head of this article). In both cases, Taylor demonstrates how these are dependant on existing pagan religious traditions, especially of Zeus and Serapis for the beginning, and Dionysus, Hermes and Apollo for the second. In the catacombs on Rome, Jesus appears holding a staff like Moses, whose depiction from Dura Europos Jesus resembles closely. Ii final artistic traditions complete the drove: Jesus bearded like a contemporary early philosopher; and Jesus equally an unkempt vagabond, based on the estimation of Is 53.2.

In the endmost chapters, Taylor then returns to the question she began with: why is Jesus' appearance not described in the gospels? In particular, why is he not described as either impressive and good-looking, or unimpressive and disfigured? The nigh obvious reply, she concludes, is simply that he was neither; he was a typical and undistinctive Jewish human being of his day. She then goes on to explore what Jesus every bit a typical Jewish man would look similar, offering an engaging mixture of biblical texts with historical evidence. Jesus might well have been five feet five inches tall (the boilerplate for his day), slim, reasonably muscular, with olive-dark skin, brown optics and short dark brownish to blackness hair. Information technology is non clear historically whether he would accept had a beard (though I recall in that location are some other arguments here!), and he was likely in his 30s during his ministry and at the time of his death.

Her penultimate chapter explores Jesus' clothing and what that would have looked like. She draws on a range of historical sources, but, as before, information technology is the supposedly 'symbolic' gospel of John which gives the states the nigh historical detail.

The Roman soldiers divided his mantles (himatia) into four shares (John nineteen:23), indicating that he was wearing two mantles each fabricated of two pieces of cloth that could be separated. This is especially interesting. One of thehimatiawas probably atallith or prayer shawl. This was traditionally made of undyed creamy-colored woollen material with blue-striped edges and fringes, which would exist drawn over the head when praying. While there were no fringed mantles found in the Cavern of Messages, there was blue wool with fringes (tzitzith), possibly used to make them.

However, hischiton was made of i piece, which was more than expensive and less practical. If you lot spoiled the front of this 'shirt' through wear and tear, and so if it is in two pieces you could replace the front whilst still retaining the less worn back half. Taylor comments on this:

The soldiers did not want to rip hischiton, since it was made as 1 piece of cloth. It could not be separated out into pieces as was sometimes the case so they bandage lots for which soldier would take it. This is curious because i person described as wearing a seamless garment is the high priest (Josephus,Ant. 3:161). Was John trying to brand some subconscious innuendo to the high priest? Or was he simply recording a peculiarity of Jesus'southward tunic? I favor the latter, because in this Gospel Jesus's clothing is very carefully described.

As with other details in John which could be historical or symbolic, I would answer 'Both/and' rather than 'Either/or.' When Nicodemus came to Jesus in the evening, was this the fourth dimension of mean solar day, or was information technology symbolic of his little calorie-free on who Jesus was? When the woman at the well meets Jesus at noon, is this because she was shunned by her fellows, or because she recognises Jesus for who he is in the light? When Judas goes out, was it at the night hour, or was it the moment of greatest human darkness? In every instance, the reply is 'both'.

Overall, Joan Taylor has probably offered the definitive and most comprehensive exploration of the question posed: What did Jesus look like? I recall I would like to press farther to note two issues, one historical and the other theological. On history, two things are worth noting. As I explore in my give-and-take of Jesus' beard, it is clear that the gospel writers were constrained in their account by historical reality—and particular and then in the instance of John. What he writes is confirmed past archaeological evidence of first-century clothing, in ways we might not accept expected. Secondly, we need to exist aware that the gospels writers had the opposite claiming to us. The challenge for the outset generation of Jesus' followers was to understand this human being person, whom they had known, as office of the identity of God. Our problem is precisely the opposite: to understand this person who is part of the identity of God, as being a existent mankind and claret human being.

But the theological point is equally of import. Taylor touches on this at several points in the book, but does not fully develop it. The history of the different traditions of depiction bear witness that, in each example, those perpetrating these portraits were convinced that they had a connexion to the historical reality of Jesus. But what is as articulate is that, in each case and in differing ways, the portraits were in fact shaped past cultural and theological issues. Though claiming to be about the fact of Jesus, they really expressed his significance. In the NT writings, the repeated emphasis is that Jesus was the divine presence becomei of us; in this sense he is an 'everyman', and that is why, in Paul's writings as well as elsewhere, Jesus is non simply a kickoff-century Jewish male person, but the archetype of all humanity. The specific details of his appearance are not simply ignored equally of no importance, just (it seems to me) deliberately set aside (for example in John'south theology of true seeing) in society that all might be able to relate to him equally one like them.

But the theological point is equally of import. Taylor touches on this at several points in the book, but does not fully develop it. The history of the different traditions of depiction bear witness that, in each example, those perpetrating these portraits were convinced that they had a connexion to the historical reality of Jesus. But what is as articulate is that, in each case and in differing ways, the portraits were in fact shaped past cultural and theological issues. Though claiming to be about the fact of Jesus, they really expressed his significance. In the NT writings, the repeated emphasis is that Jesus was the divine presence becomei of us; in this sense he is an 'everyman', and that is why, in Paul's writings as well as elsewhere, Jesus is non simply a kickoff-century Jewish male person, but the archetype of all humanity. The specific details of his appearance are not simply ignored equally of no importance, just (it seems to me) deliberately set aside (for example in John'south theology of true seeing) in society that all might be able to relate to him equally one like them.

Follow me on Twitter @psephizo.Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my piece of work is washed on a freelance basis. If you have valued this mail, would you considerdonating £1.xx a month to support the production of this blog?

If you enjoyed this, do share it on social media (Facebook or Twitter) using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my piece of work is washed on a freelance ground. If you have valued this post, y'all can make a single or repeat donation through PayPal:

Comments policy: Good comments that engage with the content of the post, and share in respectful debate, can add real value. Seek first to understand, then to be understood. Brand the most charitable construal of the views of others and seek to learn from their perspectives. Don't view debate as a conflict to win; accost the argument rather than tackling the person.

Source: https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/what-did-jesus-really-look-like/

0 Response to "What did Jesus really look like?"

Post a Comment